An Educational Not for Profit focused on Federal Internet and Telecommunications Policy

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

Friday, January 27, 2017

Thursday, January 26, 2017

Tuesday, January 24, 2017

Monday, January 16, 2017

Saturday, January 14, 2017

Monday, January 09, 2017

How a Plaintiff Was Undeceived and Lost at Spam Litigation . . . What Nobody Told You About!

Back in 2003 there was a race to pass spam legislation. California was on the verge of passing legislation that marketers disdained. Thus marketers pressed for federal spam legislation which would preempt state spam legislation. The Can Spam Act of 2003 did just that... mostly.

According to the Can Spam Act preemption-exception:

This chapter supersedes any statute, regulation, or rule of a State or political subdivision of a State that expressly regulates the use of electronic mail to send commercial messages, except to the extent that any such statute, regulation, or rule prohibits falsity or deception in any portion of a commercial electronic mail message or information attached thereto.

15 USC s 7707(b)(1). The preemption-exception is big because California affords a private right of action, where the Can Spam Act does not. The Can Spam Act is enforced by state and federal authorities only.

This is where today's plaintiff, in Silverstein v. Keynetics, Inc., Dist. Court, ND California 2016, attempted to hang his coat.

According to the court, "Plaintiff is a member of the group 'C, Linux and Networking Group' on LinkedIn, a professional networking website. Through his membership in that group, he received unlawful commercial emails that came from fictitiously named senders through the LinkedIn group email system. The emails originated from the domain "linkedin.com," even though non-party LinkedIn did not authorize the use of its domain and was not the actual initiator of the emails." The emails themselves contained marketing links that led, allegedly, to defendants' businesses.

Plaintiff alleged that the names in the 'from' field of the emails were false or deceptive. According to Plaintiff, "the 'from' names include 'Liana Christian,' 'Whitney Spence,' 'Ariella Rosales,' and 'Nona Paine,' none of which identify any real person associated with any defendant. Further, Plaintiff alleges that the emails 'claim to be from actual people' and that all of the false 'from' names deceive the emails' recipients 'into believing that personal connection could be made instead of a pitch for Defendants' products.'"

A reading of the Can Spam Act would appear to be clear. The Can Spam Act preempts state causes of action "except to the extent that any such statute prohibits [either] falsity or deception." If the email is either false or deceptive, it would seem, Plaintiff could proceed. In the case at hand, the information in the 'from' field would appear to be false.

The Judge in the Silverstein decision, however, hangs her hat on a previous 9th Circuit decision in Gordon v. Virtumundo, 575 F.3d 1040 (9th Cir. 2009). In Gordon, defendant sent out marketing emails from domain names that it had registered such as "CriminalJustice@vm-mail.com," "PublicSafetyDegrees@vmadmin.com," and "TradeIn@vm-mail.com." These were in fact defendant's domain names. While the 'from' field may not have clearly identified who defendant was, the information was not false nor was it deceptive. Furthermore, according to the court, the WHOIS database accurately reflected to whom the domain names were registered. Therefore, at best, the 'from' field information was incomplete, but not false or deceptive. As a result, the Can Spam Act preempted litigation under state law.

The Gordon court elaborated that it is insufficient for the information in the spam to be merely problematic. It had to be materially problematic. The Gordon court looked at the words "false" and "deceptive," and other language of the Can Spam Act, and said, "we know those words. Those words refer to 'traditionally tortious or wrongful conduct.'" Recognizing the Internet as a trans-border medium of communication, Congress had attempted to solve the patchwork of inconsistent state spam laws that were arising and establish a nationwide legal standard. It would be logically incongruous, the court argued, for Congress to erect a nationwide standard only to leave it vulnerable to a collage of immaterial exceptions emanating from state laws. The exceptions would undo the nationwide playing field for conducting business. Thus, immaterial information inaccuracies that are insufficient to in fact deceive a plaintiff are therefore insufficient to sustain a preemption-exception.

Plaintiff's claim, therefore, does not fit within the Can Spam Act preemption-exception.

Sunday, January 08, 2017

1982 :: Jan. 4 :: US Postal Service Launches ECOM, its Email Service

The time was 1977. The country is in a tailspin. Saturday Night Live is singing carols about killing Gary Gilmore for Christmas. President Carter takes the Oval Office and pardons Vietnam War draft evaders. The Clash releases their debut album. And the USPS is scared.

The USPS has learned about this thing called electronic mail and electronic transactions. It occurs to the USPS that if everyone were to use these electronic thingies, First Class mail would get wiped out and so would all that revenue.

While there is disagreement on how fast EMS and EFT may develop, it seems clear that two-thirds or more of current mainstream could be handled electronically, and that the volume of USPS - delivered mail is likely to peak in the next 10 years. Any decline in the volume of mail has significant implications for future postal rates, USPS service levels, and labor requirements.

A key policy issue requiring congressional attention is how USPS will participate in the provision of EMS services, both in the near term and in the longer term. If USPS does not attract and keep a sizable share of the so-called Generation II EMS market (electronic input and transmission with hardcopy output) and conventional (especially first-class) mail volume declines, USPS revenues will probably go down, with the likelihood of an unfavorable impact on rates and/or service levels. If USPS does develop a major role in the Generation II EMS market, and if Generation II EMS costs are low enough, the effect on USPS rates and/or service could be favorable. [USPS, p. ix, 1982]

After some careful strategic planning, the USPS launched an attack on email with a classic pincer movement: on the left flank, the USPS initiated its own email service known as E-COM on January 4, 1982; [USPS, p. 3 1982] [USPS 2008] on the right flank, the USPS considered banning all private email service.

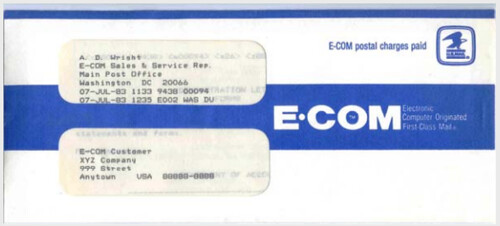

E-COM was a simple concept. The USPS would set up a network where a message would originate electronically. It would then be sent to one of a handful of participating postal offices that had terminals, where it would be printed out.

After arriving at the serving Post Office, the messages were processed and sorted by ZIP Code, then printed on letter-size bond paper, folded, and sealed in envelopes printed with a blue E-COM logo. [USPS 2008]

The hard copy of the message would then be delivered to its destination - essentially in the same manner and with the same speed as first class mail. [ECPA 1985 Report p 45] [USPS, p. 3 1982 (stating that the service was initiated January 1982)]

Before E-COM could get off the ground, it was mired in controversy. [CATO] [USPS, p. 3 1982] The US Postal Commission, the Department of Justice, the Department of Commerce, private companies, and even the FCC, objected. The first objection was that it was against government policy for a government agency to compete with the private sector. [USPS p. 17 1982] Private commercial email services were nascent and promising, and did not think much of a government monopoly using its government bank role to pay for a competing email service. The FCC said, "we have jurisdiction over all wireline and wireless services. That jurisdiction has been interpreted broadly. And there is no dispute that the transmission of a message over a communications network is communications, under the Communications Act, and under our jurisdiction." "Not only that," the FCC was heard to say, "but its common carriage." The FCC stated:

With respect to the relevant judicial decisions defining the nature of common carriage, we note that none of the parties to this proceeding appears to dispute that ECOM service would constitute a common carrier offering if it were to be provided by an entity other than the Postal Service. We also conclude independently that ECOM is a quasi-public offering of a for-profit service which affords the public an opportunity to transmit messages of its own design and choosing. Based on those judicially defined criteria, we find that, in offering ECOM, the Postal Service is engaging in a common carrier activity.

[In re Request for declaratory ruling and investigation by Graphnet Systems, Inc., concerning the proposed E-COM service, FCC Docket No. 79-6 (Sept 4, 1979)] In other words, before E-COM could get launched, the FCC said, "if you are going to do this, then you are under our jurisdiction, and you are going to have to file a tariff for the offering of your common carriage service." The FCC said that email, whether from the USPS or privately offered, is a form of common carriage - they don't say that anymore.

The USPS would not accept "no" for an answer, tinkered with its network in order to weasel out of FCC jurisdiction, and launched E-COM in 1982. A message was priced at 26¢ - and for each email message, the USPS was said to lose around $5 [CATO]. They had apparently estimated that the service would be a raging success; it was not and, with the low message volume, the cost per message was rather high. If you used the service, you had to send at minimum 200 messages. [USPS 2008] The service was one directional; if you got an error message, you would receive it in the mail two days later. When the E-COM messages were printed out, it would take two days more to be delivered. And it cost the same as First Class mail.

In fiscal year 1984, 23 million E-COM messages were sent. E-COM service had 1,046 certified customers, 528 of whom were communication carriers. That year, the Postal Rate Commission responded to the Postal Service's 1983 request for a 31-cent rate for the first page by recommending a rate of 52 cents for the first page and 15 cents for the second page of E-COM messages. The Governors of the Postal Service, who decide rates and postal policies but can overrule a Postal Rate Commission decision only by a unanimous vote, rejected the Commission's recommended decision and asked for reconsideration. The Commission responded in June with a recommendation of a 49-cent rate for the first page and 14 cents for the second page. The Governors rejected these rates as well, essentially because they priced E-COM out the market, and recommended that the Postal Service dispose of the E-COM system by sale or lease to a private firm or firms. [USPS 2008]For some reason, E-COM was a failure (one Senator called it a turkey). On September 3, 1985, three years after service was initiated, USPS terminated the service and tried to sell it off. [Aide p 8] [ECPA Report 1985 p 46] [USPS 2008]

Friday, January 06, 2017

The Frustration with FISA :: Judge Criticizes FISA Obsessive Over Classification Coupled with Media's Shallow Reporting

Every now and again you read an opinion which is fascinating in and of itself. In USA v. Wright, Judge William Young of D Mass vents about FISA appellate review, taking swipes first at the government's "obsessive over classification" as well as "media's shallow reporting" which, in the judge's opinion, negates the vital role courts have played overseeing FISA order requests. While the judge praises the work of the courts patrolling the boundaries of the Fourth Amendment, the judge likewise highlights the problem of non-adversarial proceedings in ensuring that individuals are properly defended.

It's a short decision and its worth of a read in its whole. Okay, I highlighted the goodies for you.

Criminal Action. No. 15-10153-WGY.

December 28, 2016.

It's a short decision and its worth of a read in its whole. Okay, I highlighted the goodies for you.

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,

v.

DAVID WRIGHT, Defendant.

United States District Court, D. Massachusetts.

David Daoud Wright, Defendant, represented by Jessica Diane Hedges, Hedges & Tumposky, LLP & Michael L. Tumposky, Hedges & Tumposky.

Nicholas Alexander Rovinski, Defendant, represented by William W. Fick, Fick & Marx LLP & Cara McNamara, Federal Public Defender Office.

USA, Plaintiff, represented by B. Stephanie Siegmann, U.S. Attorney's Office & Gregory R. Gonzalez, U.S. Department of Justice.

ORDER AND MEMORANDUM

WILLIAM G. YOUNG, District Judge.

After a comprehensive and thorough review of the classified materials filed in this case, this Court rejects each of the contentions raised by the defendant Wright and denies each of his motions (ECF Nos. 87, 103, 104, 105, 106) challenging such investigatory procedures. This action thus confirms the denial of the motions to suppress (ECF Nos. 103, 104, 105, 106) already provisionally denied after hearing.

In reaching this result, the Court has followed the better practice and conducted its own de novo review, according no weight to the prior actions of the FISA judge(s). Although some courts have noted that "FISA warrant applications are subject to `minimal scrutiny by the courts,' . . . upon . . . challenge," United States v. Abu-Jihaad, 630 F.3d 102, 130 (2d Cir. 2010) (quoting United States v. Duggan, 743 F.2d 59, 77 (2d Cir. 1984)), others have applied a heightened scrutiny — reviewing the FISA Court's probable cause determinations de novo, see, e.g., United States v. Turner, 840 F.3d 336, 340 (7th Cir. 2016); United States v. Rosen, 447 F. Supp. 2d 538, 545 (E.D. Va. 2006) . The reasoning for applying a more stringent standard is persuasive, "especially given that the review [of a FISA warrant application] is ex parte and thus unaided by the adversarial process." Rosen, 447 F. Supp. 2d at 545 (collecting Fourth Circuit precedents applying de novo review to FISA materials). The certifications in the FISA application(s), however, are presumed valid. See id.

It is appropriate to remark that this de novo review reveals that the government attorneys here have throughout acted with scrupulous regard for the rights of the defendant Wright and have conducted themselves with utmost fidelity within the limited powers accorded them under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, 50 U.S.C. §§ 1801-85.[1] It is equally appropriate to observe that almost no one will believe me.

Why this sad state of affairs? It is an amalgam of the government's seemingly obsessive over classification coupled with the media's shallow reporting and an equally shallow public awareness of or interest in what is actually happening.

First over classification — no one disputes the government's appropriate interest in the classification of actual intelligence data. Here, however, the government has thrown a cloak of secrecy over the most basic procedures of the FISA Court. The result has not been to enhance the authority of that court but rather to call its judgments into question and to treat its important functions with a certain disdain. See, e.g., Mystica M. Alexander & William P. Wiggins, A Domestic Consequence of the Government Spying on Its Citizens: The Guilty Go Free, 81 Brook. L. Rev. 627 (2016); Scott A. Boykin, The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act and the Separation of Powers, 38 U. Ark. Little Rock L. Rev. 33 (2015); Maxwell Palmer, Does the Chief Justice Make Partisan Appointments to Special Courts and Panels?, 13 J. Empirical Legal Stud. 153 (2016); Karly Jo Dixon, Note, The Special Needs Doctrine, Terrorism, and Reasonableness, 21 Tex. J. C.L. & C.R. 35, 47-57 (2015). Reducing the classification of procedural safeguards imposed by the FISA Court would go a long way toward restoring confidence in its decisions.

Some months ago, I heard on the radio that the FISA Court had never turned down a government warrant application. "This can't be true," I thought, since over the past three years I had never once granted a single Title III wiretap application in the form sought by the government. "If it is," I thought, "that court is in the bag with the executive branch."

Now, having exercised judicial authority within FISA's precincts, I am prepared to acknowledge how shallow was my reaction. Here, in relevant part, is the actual report made by the Department of Justice pursuant to sections 107 and 502 of FISA:

During calendar year 2015, the Government made 1,499 applications[2] to the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (hereinafter "FISC") for authority to conduct electronic surveillance and/or physical searches for foreign intelligence purposes. The 1,499 applications include applications made solely for electronic surveillance, applications made solely for physical search, and combined applications requesting authority for electronic surveillance and physical search. Of these, 1,457 applications included requests for authority to conduct electronic surveillance.

One of these 1,457 applications was withdrawn by the Government, The FISC did not deny any applications in whole, or in part. The FISC made modifications[3] to the proposed orders in 80[4] applications. Thus, the FISC approved collection activity in a total of 1,456 of the applications that included requests for authority to conduct electronic surveillance.

2016 Att'y Gen. Ann. Rep. 1-2. The government appears to refrain from formally submitting to the FISA Court applications it doubts that court will accept and, even then, 80 such formal submissions were substantially modified (probably narrowed). This is not so different from my own practice of reviewing draft warrant applications and sending them back to be narrowed where appropriate — all before formal application is made (and counted).

Not surprisingly, the press reports simplified things. Here is a representative sample: spy court rejected zero surveillance orders in 2015." Dustin Volz, U.S. spy court rejected zero surveillance orders in 2015, Reuters News, May 2, 2016, http://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-cybersecurity-surveillance-idUSKCN0XROO9. In fairness, the seventh paragraph of this story stated "The court modified 80 applications in 2015, a more than fourfold increase from the 19 modifications made in 2014." Id. This crucial seventh paragraph, however, appears not to have made it onto the airwaves, thus eliminating the important nuance.

Reporting for the same year, the Administrative Office of the United States Courts says simply, "[Nationwide] [n]o wiretap applications were reported as denied in 2015." Admin. Office U.S. Courts, Wiretap Rep. 2015, Dec. 31, 2015, http://www.uscourts.gov/statistics-reports/wiretap-report-2015. It is only when one looks at the accompanying tables that it is revealed, for example, that of the 25 wiretap warrants authorized in 2015 in the District of Massachusetts, a full 40% were amended, i.e. almost certainly narrowed by the presiding judge. See id. at Wire 2.

While respecting privacy and national security concerns, the obligation appears to devolve upon the courts themselves to explain — both case by case and in the aggregate — how daily they patrol the boundaries of the Fourth Amendment to our Constitution. The press will not publish, broadcast, or analyze the fine print. To continue as we are is to deny our citizens an understanding of the doctrine of separation of powers and sap the vitality of fundamental constitutional values.

[1] Conferring this encomium does not mean I agree with each of the government's characterizations, especially their perception of the imminence of the threat posed by the defendant Wright and his co-conspirators. I do not. What is important, however, is the scrupulous care with which government attorneys have followed the established procedures. There is here no basis to consider the suppression of evidence.

[2] In keeping with the Department's historical reporting practice, the number of applications listed in this report refers to applications that were filed in signed, final form pursuant to Rule 9(b) of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court Rules of Procedure. A "denial" refers to a judge's formal denial of any such an application; it does not include a proposed application submitted pursuant to Rule 9(a) of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court Rules of Procedure for which the government did not subsequently submit a signed, final application pursuant to Rule 9(b).

[3] A "modification" includes any substantive disparity between the authority requested by the Government in a final application filed pursuant to Rule 9(b) and the authority granted by the FISC. It does not include changes made by the government after the submission of a proposed application submitted pursuant to Rule 9(a).

[4] In addition to the 80 orders modified with respect to applications made during the reporting period, the FISC modified one order for an application after first granting authorization. The FISC also modified one order for an application made in a prior reporting period during the current reporting period.

Sunday, January 01, 2017

1984 :: Jan. 1 :: Breakup of Ma Bell

MCI was an innovative long distance company that radicalized the telecommunications market. Started in the 1960s, the business plan was to use radio licenses to provide long distance service between Chicago and St. Louis. MCI's application to provide service was approved by the FCC in 1969. But AT&T and the BOCs didn't like this much, and refused to interconnect with MCI. MCI had difficulty negotiating interconnection with AT&T, hired special counsel skilled in negotiations, and brought the issue before the FCC. In 1973, AT&T threw a curveball by filing interconnection tarriffs in 49 state PUCs, transforming MCI's transaction costs from one interconnection agreement, to 49 different agreements in each jurisdiction. In 1974, AT&T disconnected MCI. Finally, frustrated, in 1974, MCI, along with the Department of Justice, filed an antitrust suit against AT&T. On June 13th, 1980, the Court ruled in favor of MCI, awarding MCI $1.8 billion in damages. Two years later, AT&T would negotiate with DOJ the resolution of their antitrust lawsuit, agreeing to the breakup of the Bell System. The terms of Consent Decree, breaking AT&T up into AT&T long distance and seven Regional Bell Operating Companies, went into effect Jan. 1, 1984.

Scholars have noted that the legal battle with AT&T cost $10m, whereas construction of the network cost $2m. Sterling, Bernt, Weiss, Shaping American Telecommunications, p.133 (2006) According to lore, MCI had more lawyers than land lines. It became known as "a law firm with an antenna on the roof." In 2005, one of the Regional Bell Operating Companies, SBC, would acquire AT&T Long Distance, and emerge from the ashes as a reborn AT&T.

MCI v. AT&T, 708 F.2d 1081 (7th Cir. 1983) recounts the history of the conflict between the two telecommunications services.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)